My Final Year Project (I): Counting Geodesics

01 Apr 2019I have just finished the final presentation for my undergrad thesis, titled Bicuspidal Geodesics on Punctured Hyperbolic Surfaces. (The slides are available on my portfolio page.) As such, I’m taking this opportunity to briefly describe my project.

Geometry on surfaces

My project takes place in the setting of geometry on surfaces. In particular, this means that the surface comes equipped with a way to measure lengths and angles (more formally, a Riemannian metric).

Once we have the notion of length and angle, we can talk about the geodesics on the surface, or “straight lines” relative to the surface. For instance, the geodesics on a sphere are the great circles; on the Earth, some examples are the equator and the lines of constant longitude.

Now we can study the set of lengths of (certain classes of) geodesics, which we can call the length spectrum. Most interesting classes of geodesics have infinitely many members, so we can ask about asymptotics: how many geodesics (in a certain class) have length $\leq L$?

As we shall see, this question is interesting not only because it arises naturally from geometry; sometimes the lengths of geodesics on particular surfaces have alternative interpretations in number theory.

First examples: flat tori

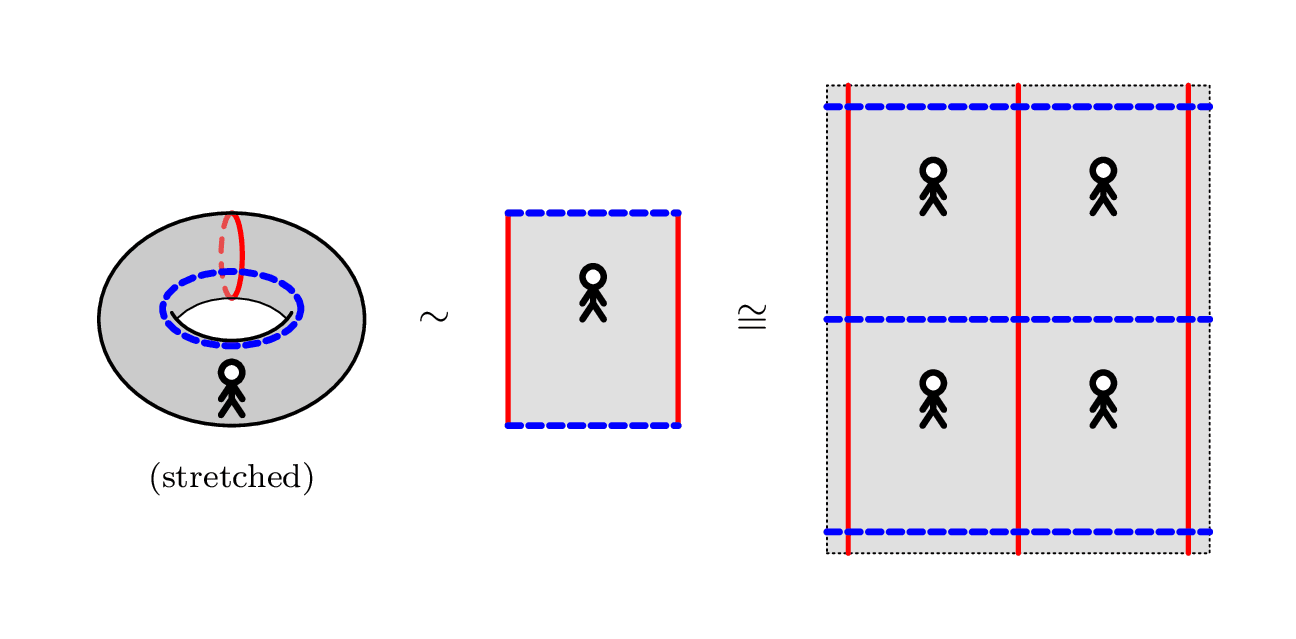

Our first example is the class of flat tori. A flat torus is the surface obtained by gluing the opposite sides of a parallelogram in the Euclidean plane $\bb R^2$ (figure, centre).

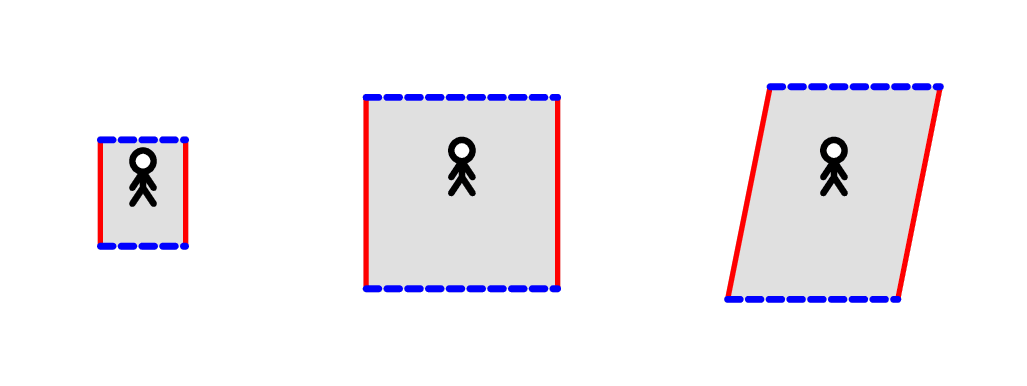

Since the flat torus is locally isometric to the Euclidean plane, it has $\bb R^2$ as its universal covering space (right). All flat tori are homeomorphic to the torus (left), but there are many flat tori which are geometrically different from (ie. non-isometric) the one pictured above, such as the following:

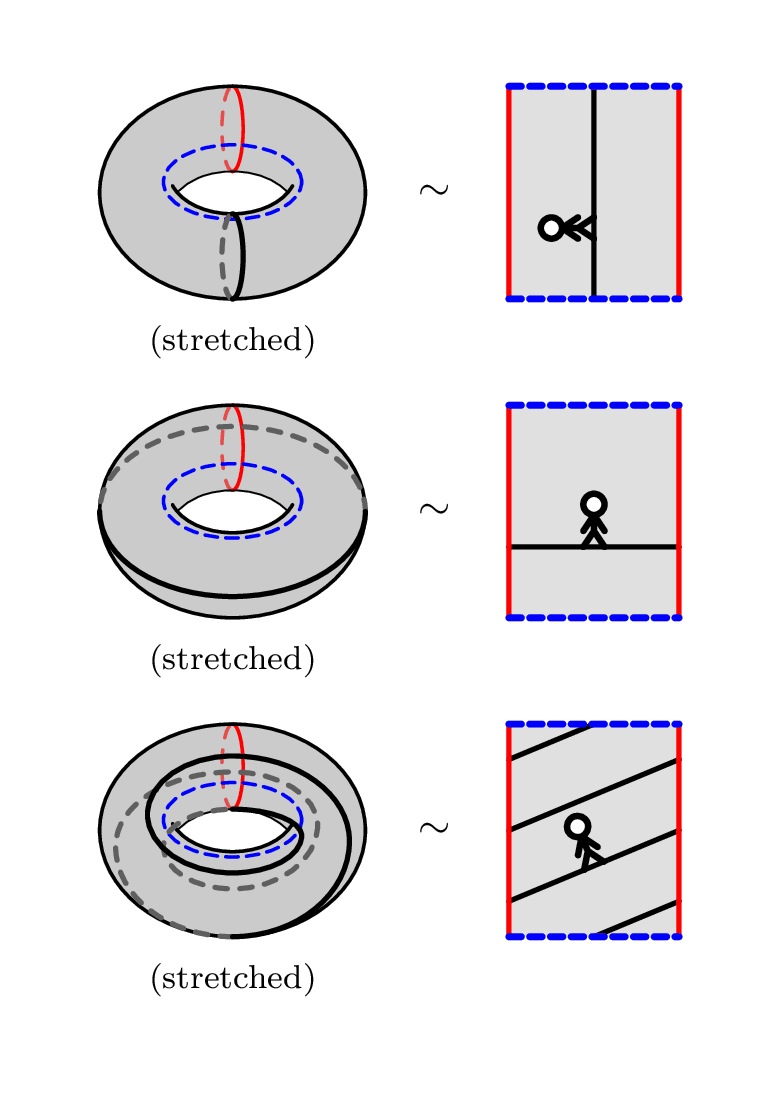

Given a flat torus $S$, consider the set of closed geodesics on a flat torus which start from a given point $p$ (pictured as a stickman). Here are some examples, with the corresponding topological picture:

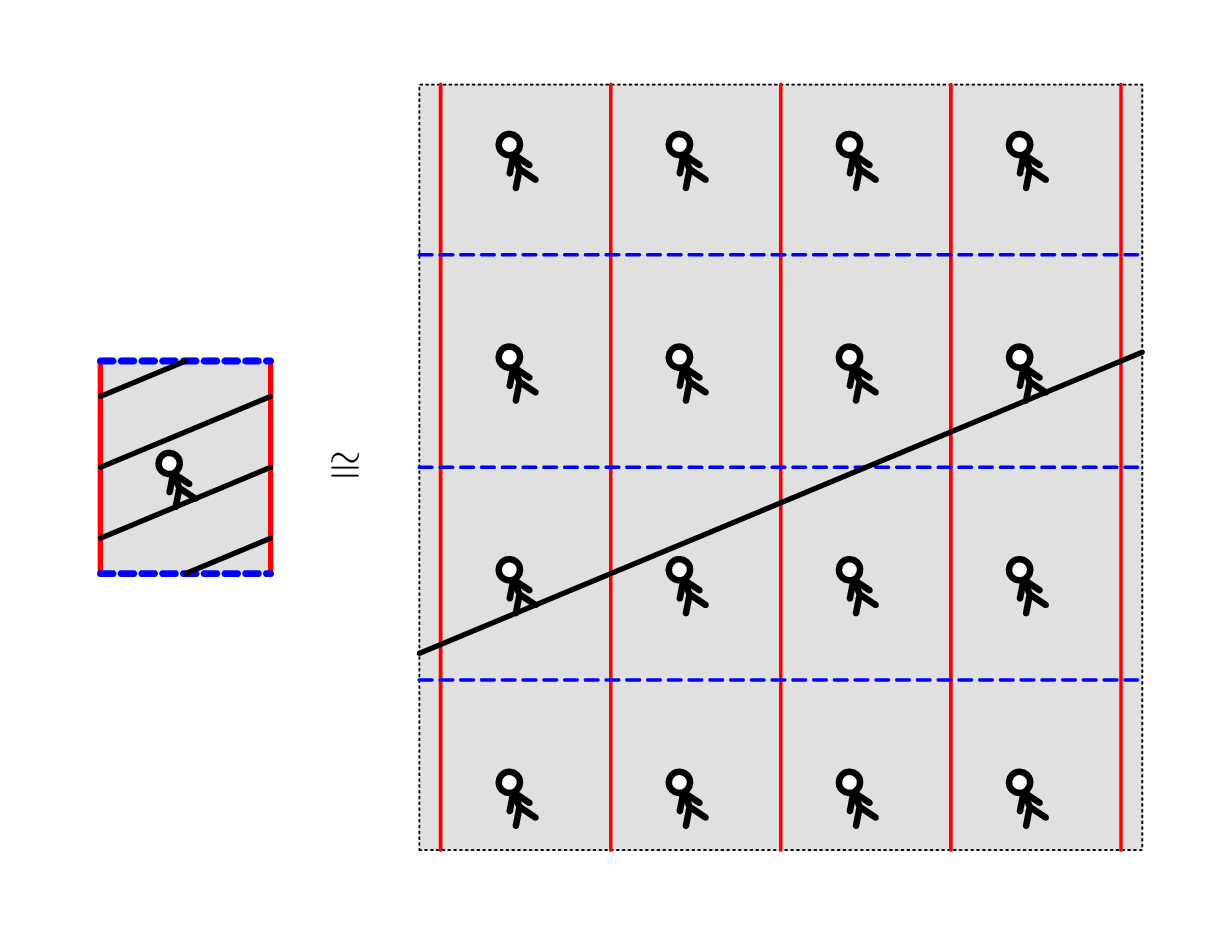

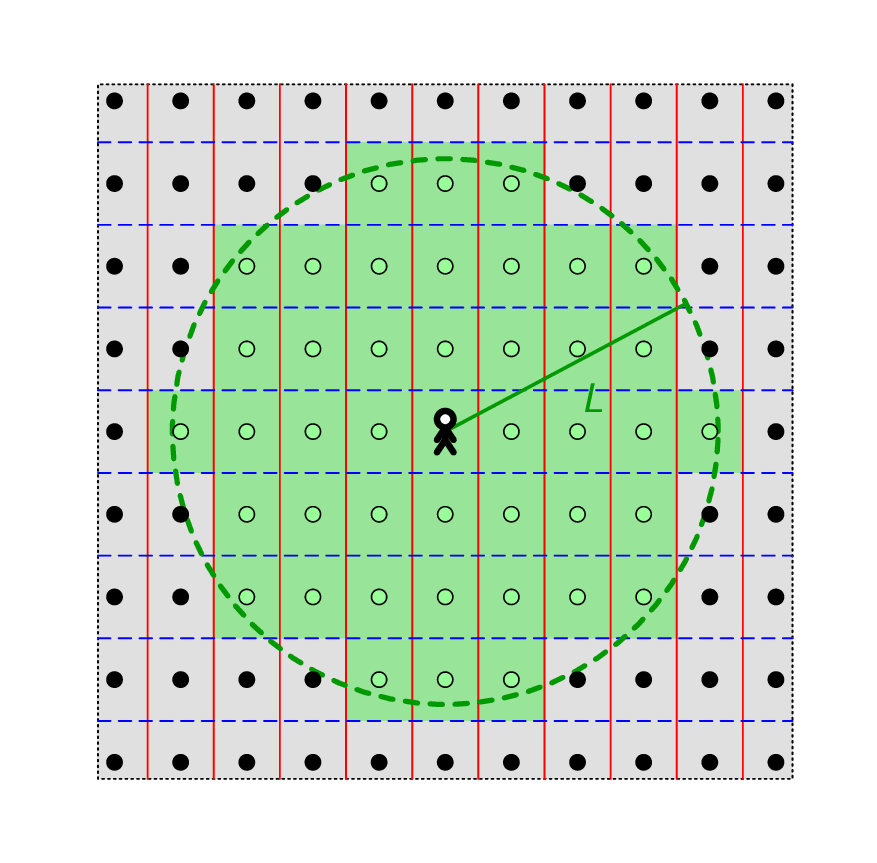

To simplify matters, we include geodesics that traverse a loop multiple times, or in opposite directions, or even the trivial geodesic of length $0$. In this case, every closed geodesic corresponds to exactly one lift of $p$ in $\bb R^2$:

Asymptotics for closed geodesics

We can now derive the asymptotics for the number of closed geodesics on $S$ starting from $p$. By the previous discussion, the number of such geodesics of length $\leq L$ is precisely the number of lifts of $p$ contained in a circle of radius $L$:

On one hand, the green shaded area is equal to

On the other hand, one can show that there exists a constant $c_S>0$ such that the green area contains the circle of radius $L-c_S$, and is contained in the circle of radius $L+c_S$. Hence this area is $\pi L^2+O(L)$, so we have

Improving the error term above is a long-standing open problem known as the Gauss circle problem. The conjectured true error is $O(L^{1/2+\eps})$, while the best known error bound is $O(L^{0.6298\ldots})$.

Application to number theory

For some surfaces, the length spectrum of closed geodesics has a natural number theoretic interpretation. For instance, suppose we are interested in the number of ways to write integers up to $1000$ as sums of two squares. In other words, we want to find

But by the geometric picture in the previous section, this is equal to the number of closed geodesics on $S$ from a point with length $\leq L$, where $S$ is the square torus of area $1$ (so that lifts of the point $p$ to $\bb R^2$ form the integer lattice $\bb Z^2$), and $L=\sqrt{1000}$. Hence this count is approximately

This is pretty close to the actual count of $3149$.

Conclusion

In this post, we have seen a toy case of the question of counting geodesics on surfaces, namely for flat tori, and we already saw its connections to areas outside of geometry. In the next few posts, we will consider the same question for a much larger class of surfaces, coming from hyperbolic geometry.

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!